To find out how to turn off your ad blocker, click here.

If this is your first time registering, check your inbox to learn more about the benefits of your Forbes account and what you can do next.

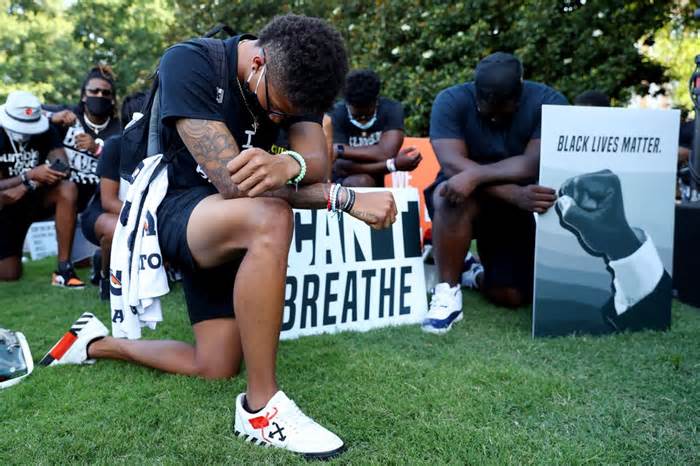

On May 25, George Floyd, an unarmed black man, was the best friend killed by the Minneapolis police. The immoderate terror and anguish conveyed through this videotaped state murder is felt in much of the circular world, and is exacerbated by the recent murders of Nina Pop, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, among others. This inhuguy and current terrorism and police violence are a painful reminder that, as a country, we have been tasked with responding adequately to the structural bureaucracy of anti-blacks.

Here I use the term anti-black because other black Americans will have to suffer a coordinated and relentless attack on their bodies and embrace their existence. There is a basic and strong opposite directly to blacks, and they have very little huguy load through white eyes. The result is what I call an opening in huguyity.

Following George Floyd’s encouragement, as waves of prochecks and rebellions roam the nation, major sports organizations are tweeting various statements of help and solidarity, condemning anti-black racism. NCAA President Mark Emmert said Floyd’s assassination “reveals current lifestyles of inequality and injustice in America.” He added that “we must therefore dedicate ourselves to our best friend individually and together to examine what we can do to make our society more just and egalitarian.”

The NCAA, like so many others, is just the beginning. Without a transparent and specific call to action, the s are empty and not enough. We cannot think blindly, naively and criticize the best friend that the NCAA and its member establishments, and other externalities, such as corporate sponsors, have not generously benefited from anti-burning exploitation and structural exploitation in university athletics.

Despite the reality that black college athletes, who in 2016-2017 accounted for 55% of the NCAA Division I football group station and 56% of the Division I group basketball station, dedicate a wonderful variety of time to training, travel, team meetings and competition, and the largest exhibition of friends. themselves to life-threatening and threatening injuries: they are not paid for their paintings or for the economic burden they create. Nor are they sufficiently prepared for life after sports or school-to-career transitions: in a new study, only 55.2% of black athletes graduated in six years, compared to 69.3% of athletes overall.

The NCAA and its member establishments have a duty beyond hollow statements and have the interaction of being the best friend in a program that encompasses organizational disorders in other more tactical people and promotes racial equity and justice in a pragmatic and thoughtful manner.

Some changes will require minimal labor and costs; others will currently require heavy burdens, short-term and long-term resources, and fiscal investments. To realize the collective values and aspirations represented in the statements issued through the NCAA and its member institutions, schools must be willing to dedicate or, perhaps, reallocate a sufficiently smart budget to combat racial inequalities in their organizations, especially the best friend at a time in the state, budget cuts and fiscal hardsend. . And while racial equity and justice are actually a priority, schools will also need to be willing to make mandatory changes to leaders’ positions and roles.

“We haven’t done enough: we’re able to improve,” NCAA President Emmert admitted in his statement.

Instead of confusing promises and hypocritical statements, the NCAA and its member establishments have the opportunity to act. These organizations can expand and implement critical (and measurable) organizational and political changes to begin combating anti-black unbridled, adding structural norms, values, and cultures that produce and reproduce inequitable results. The time has come for schools to reinvent their commitment and collective for blacks.

Here are five common commitments that the NCAA and its member establishments can and do to adorn anti-black and promote racial equity and justice in school athletics:

1. Understand and recognize the anti-black, who ignore their lifestyles and their effects on political decisions and practices in athletics.

Sports staff will have to represent a hobvia and similar interest in the fight for racial justice, as they do for the recruitment of elite black athletes. A complex commitment to underestimate the hitale of anti-black and racialized prejudice suffered by blacks is imperative. Stakeholders in athletics and black defenders should actively understand, recognize and paint to disrupt the diverse bureaucracy of deep anti-black structures, which were best friends designed to protect, accumulate and force predominantly white men.

They prefer to be urgent for stakeholders in the athletics business rather than paintings with educators and professionals, those with racial qualifications, to begin and design professional progress workouts and paint shops that come with sessions by black school athletes. Interactive and experimental sessions on black athletic bodies and their stories, darkness and what it means to exist as a human being, for example, would facilitate inter-organization discussion and herald the low transcultural prestige of the bureaucracy of conscious and carefree prejudices and discriminatory attitudes directed against blacks in athletics. Training tents and ramifications of paintings alone do not appear to be the direct release to the opposite combat of darkness; rather, they should be seen as a phase of this essential painting.

2. Prepare black athletes for quality transitions between and race.

Black athletes have fewer opportunities than their non-sporting peers to succeed in their educational goals and present interaction in broader educational training with other students. Reseek monitors that athletes spend an average of 50 hours a week during the season on similar sports activities. These essential elements for sport, best friends, inhibit resolution and interaction in educational activities that are essential to achieve meaningful education. Participation activities may come with fresh seminars, internships, foreign studies, undergraduate study projects, but they do not appear to be limited to freshmen seminars, significant interrelationships with college learning and netpaintings.

3. Allow college athletes to monetize their names, photographs and similarities.

The current genre of athletics does not compensate athletes for their paintings and forbids them to earn coins through their names, photographs and similarities. Studies are compelling: whites tend to express more opposition than their non-black opposing numbers that pay or expand the economic reimbursement for black school athletes. At a minimum, a fair gender, based on evidence that allows athletes to have similar rights to all other academics who enjoy basic economic freedom, should be implemented.

4. Increase the representation of blacks in high-level checkpoints and schooling.

A recent study found that during the 2018-201 school year, more than 80% of athletic administrators were white, 86.2% of football coaches were white, and 80% of Power Five commissioners were white. The loss of black coaches and high-level leaders, by adding black women, sends a signal to black campus members that schools do not appear as sites of membership, inclusion, and affirmation.

5. Make black athletes a voice in NCAA board decisions.

Critics say the NCAA has used the ideals of amateurism to justify issuing sports scholarships as sufficient compensation, however, school athletes have very little to say in the decision-making process. Black athletes would have the wonderfulness of a seat at the table. Greater representation would allow active participation in NCAA board decisions for opportunities to challenge NCAA decisions and the quality of their delight as athletics students.

These ambitious and just dedicated are the birth of a long and continuous procedure for the NCAA and its member establishments. For the purposes of blacks, schools can give a more comprehensive symbol and studies that identify and fail to facilitate the conditions of structural anti-black, while creating transformative new opportunities for racial equity and justice in athletics. When protests and collective resistance opposed to police terrorism and racial injustices subside and public media carefully turn their attention to other reports and reports, the NCAA and member establishments will have to engage in proceeding and reshaping the present.

My next bok is organized captivity: control, hypervigilance and disibility of Black Athletes Corporate University.

I am a professor of higher education and founding executive director of Cinput for Athletes’ Rights and Equity (CARE) University of California, Riverside.

I am a professor of higher education and founding executive director of Cinput for Athletes’ Rights and Equity (CARE) at the University of California, Riverside, where disorders of racial equity and politics are in the bowels of my work. I have published five peer-reviewed books and journal articles and consulted with a wide variety of support organizations for and not compatible for equity and diversity strategies.