The fortuitous discovery of lines carved into the rocks of an ancient tomb in what is now the Israeli-occupied Golan can also provide a new vision of an enigmatic culture that flourished thousands of years ago.

In a small clearing, the Yehudiya Nature Reserve, among yellow and shaded weeds through eucalyptus trees, giant rocks and dark basalt slabs form a small covered room that opens to the east.

Megalithic design is one of thousands of so-called dolmens scattered in northern Israel and the region as a whole, from burial tombs erected between 4,000 and 4,500 years during the Intermediate Bronze Age.

Today, on the plateau captured in 1967 in Syria, with Israeli infantry soldiers securing the border just 23 kilometers (1 mile), scientists are looking for the region’s remote past.

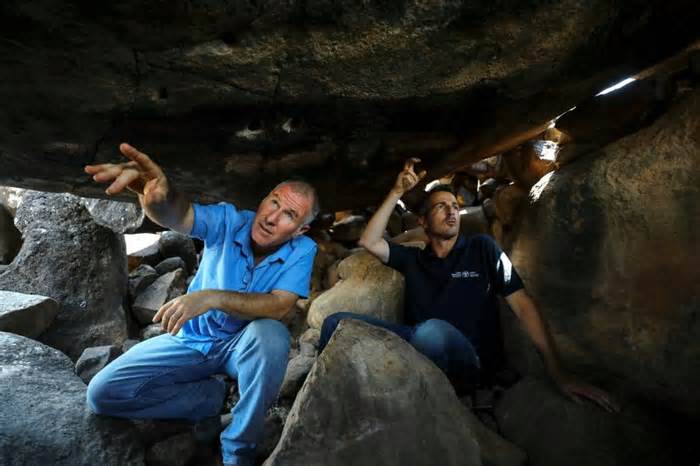

Uri Berger (R), regional archaeologist of the Israel Antiquities Authority, and Gonen Sharon, professor of archaeology at Tel-Hai College in northern Israel, provide ancient engravings and dolmen Photo: AFP / MENAHEM KAHANA

The identity and ideology of those who built the monuments on a giant component is unknown. But a new fortuitous discovery of rock art can also reposition that.

About two years ago, “when the guards here in the park were on their daily trek, she looked respectfully and saw something carved into the walls,” recalls Uri Berger, an archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority.

The park ranger contacted the IAA and “when we looked inside, we saw that it wasn’t just engraved lines or stains on the wall, it’s rock art,” Berger said.

The lines shape six animals with horns of alternate sizes, 3 facing east and 3 facing west, with two of them, a male and a female, directly facing face.

This megalithic design is one of thousands of dolmens scattered in northern Israel and the region, from burial tombs erected between 4000 and 4,500 years old in the Intermediate Bronze Age Photo: AFP / MENAHEM KAHANA

Another animal with horns is carved into a panel, in front of six.

The zoomorfa representations, hidden from the birth of the study of dolmens two hundred years ago, were the first discoveries in the region and a primary progression for Berger and his fellow student, Gonen Sharon.

Uri Berger, regional archaeologist for the Israel Antiquities Authority, stands amid an ancient structure near Kibbutz Shamir in the upper Galilee area of northern Israel Photo: AFP / MENAHEM KAHANA

Sharon, professor of archaeology at Tel-Hai College in northern Israel, is an ancient discovery.

Just north of the nature reserve, the outdoor Shamir kibbutz, north of Galilee, Sharon was walking with her teenage children in 2012 in a box with about 400 dolmens scattered.

Crawling in the shadow of the larger monument, Sharon sat down, looked at the roof of the dome’s giant sning and said she had seen “shapes” that looked like herbal formations.

“If someone had done them,” he recalls.

The marks turned out to be chain sculptures resembling tridents.

A photo monitors engravings on a rock with photographs of animals and an intermediate dolmen of the Bronze Age Photo: AFP / MENAHEM KAHANA

“It turned out to be the first done in the context of dolmens in the Middle East,” Sharon said.

Shamir’s sculptures, immaculate through generations of researchers, have revitalized the archaeological study region.

One of the sites revisited was inside an industrial zone near Kiryat Shmona, a town northwest of Shamir, where three small megalithic structures that survived the zone’s development a few decades ago are surrounded by circles of stones.

In the largest, relatively rounded dolmen, in the corner, there are two sets of short parallel lines engraved on either side of the rock, with a longer line carved under the image of closed eyes and a mouth wincing towards the sky.

“The grooves don’t seem functional,” Sharon said. “For us, they seem to be a face.”

Stone monuments have “replaced the landscape” of northern Israel, Berger said.

But their importance has also made them point to the theft of antiquities, which in giant components have stripped the maximum remains probably to produce clues about their creators.

Small ceramic pieces, spearhead classified ads and metal daggers, pieces of jewelry and classified ads and some bones are decrypted at the sites from time to time, Sharon said. “But it is not frequent to find” anything, and such unearthing are very scattered.

“We know very little about the culture of providing them.”

With the discovery of stone-carved art, “we are able to say something more than we have known for two hundred years,” Berger said.

The discoveries of rock art, published in a new article through Sharon and Berger’s Asian Archeology magazine, provide for the first time the animal drawings of this ancient culture and provide the broader genre of the region’s visual offering.

Berger said the drawings raise new questions about those created.

“Why those animals? Why in those dolmens and others? What made this special?”

The slow but steady accumulation of artistic discoveries brings researchers closer and closer to the topics in their research, “to the civilization you know,” Berger said.

For Sharon, “it’s like a letter from beyond that begins to present what global culture and symbolism is beyond undeniable design and the erection of very giant stones.”